Bridge Fishing in the Back Bays

Anglers can find great fishing for their favorite inshore species at the bridges all summer long.

It was a beautiful Tuesday in August when I chose to forgo fluke fishing for some bridge bravado. There was a high tide shortly after dawn, which was ideal because boat traffic and the corresponding wakes would be at a minimum at that time. My target species was tautog. Although I don’t mind the fast action of shorts and small keepers, larger fish in the 7- to 10-pound class were being reported, which piqued my interest in bridge fishing.

On the first drop, I felt the telltale bites of blackfish on my green crab. I thrust the rod skyward only to whiff completely in dramatic fashion. On the next attempt, I sent half a green crab to exactly the same spot, inches from the pillar, making sure it didn’t get caught in the current and pulled downstream of the structure. A moment later, tap, tap, pause, tap, tap, pause, tap … hookset! This time, the tog jig grabbed hold and the battle began. The fish ran toward the concrete fortress and made an outstanding attempt at freedom. However, I was able to pry it away from the structure, where I could play the fish without fear of getting cut off and then it to the net. On a digital scale, the blackfish settled at 9 pounds, 2 ounces. On an oceanside wreck, it would be a solid specimen—but for the inlet, it was a monster.

What makes bridge fishing so special?

In many estuaries and inlets, bridges are the only significant structure within an otherwise natural environment. Marshes and sandy bays don’t have much in terms of hard structure. In northern waters, glacial rock and boulders provide substance and profile that enhances nursery grounds; however, large, intrusive pillars create an altogether different kind of habitat that is unparalleled in backwaters.

Bridge stanchions are most often composed of concrete, but wood, steel, rebar, or modern composite materials may be used within the overall bridge construction. The more structure the better, so bridges with wider columns contain more available surface area to draw and attract marine life. Line up a long row of bridge pilings and a fish-holding habitat is created. Moreover, older bridges with cracks, chips, and other signs of wear often attract many varieties of fish and reciprocal hiding spots.

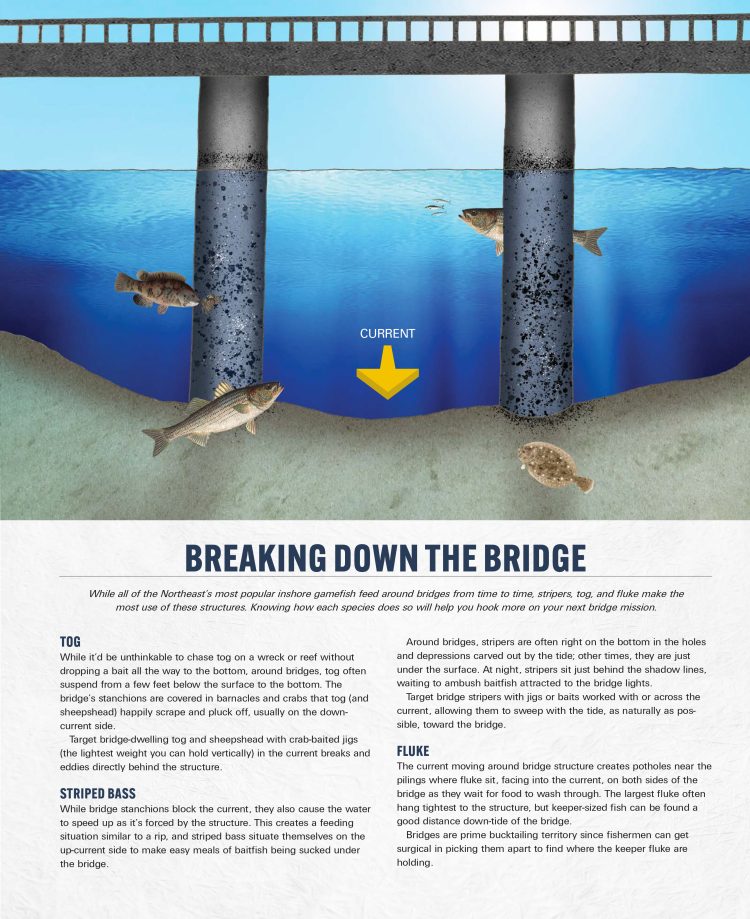

Bridges regularly cross channels of deep, tidal water that brings fish the oxygenated water they seek. The pillars create current breaks and eddies that provide ambush stations for staging fish. The breaks are substantial enough that they can affect fishing for up to 100 yards down-current. Water also swirls in the lee of the structure. This zone is perfect hunting territory compared to the surrounding waters that lack features. When the tide reverses from flood to ebb, the other side of the bridge becomes more favorable, a perpetual flip-flop that happens every day.

In addition, a scouring effect takes place around and down-current of each column. Sometimes, the depth change can be as much as 50 feet due to the current ripping past the structure and forming an abyss. In other instances, the changes might be more gradual but just as beneficial. Uneven bottom that includes smaller gullies and potholes is ideal habitat for all inshore fish.

Life abounds on and around each structure, where mussels, barnacles, and marine life attach themselves. Crabs prowl the structure’s surface while a variety of baitfish school along and huddle in the current breaks. It is common to see thousands of bay anchovies or spearing directly behind a pillar. Remember the food cycle you learned about in grammar school? It’s on full display at every bridge that crosses salt water.

Tautog and Sheepshead

Bridges are magnets for these structure-bound bruisers. They assume residence around the stanchions, picking off crabs, worms, and crustaceans. Anglers using trolling motors to hold their boats right next to the pillars then lower jigs baited with green crab, Asian shore crab, fiddler crab, rock crab, shrimp, or sand fleas. Essentially, any legal-to-use crab will catch, though whole, halved, or quartered live ones are best.

Tog bite most often on or near the bottom, but they will also swim up and down an abutment while hunting food. Sheepshead, on the other hand, swim in all depths of the water column and are more likely to be caught above bottom. Trophy sheepshead can be coaxed five feet under the surface when the water is extremely deep. Those caught in New York, New Jersey, and the Mid-Atlantic area are usually quite large and regularly break the 10-pound mark.

These catches differ from those taken from the Carolinas, where sheepshead are far more plentiful in a full range of sizes. For both tog and sheepshead, clean and clear water is the key, and although any tide can produce, the finest results will take place on higher ends of the tide. The lower end of ebb tide is often associated with more suspended sediment, water discoloration, and seaweed. April until December are the months to look for bridge blackfish (taking into consideration the closed seasons), while large-and-in-charge sheepshead prowl the pillars from June through October.

Like ocean togging, anglers can “build the bite” by spending time fishing in one location. Even missed hooksets will disperse scent and bits of crab that bring more fish to the area. On the flipside, some anglers move between bridge pilings to locate fish at different locations instead of trying to draw them in.

A trolling motor’s anchor feature is outstanding for this application, but a word of caution. If passing vessels toss a big wake, the trolling motor and bow of the vessel may get tossed into the structure, causing damage. It’s essential that jigs are dropped directly along the sides and lee of the structure. Standard jig weights run from ½ ounce to two ounces, depending on the bridge.

Anglers who allow their baits to drift back will catch far fewer blackfish. If it is a struggle to fish jigs along the structure, switch to a standard dropper rig with a bank sinker to achieve tog success. There won’t be a drop-off in tog fishing with an old-school, dropper rig, though sheepshead respond better to a jig approach in the Northeast.

Striped Bass

Flushing water, current eddies, and disoriented food fish draw stripers into the confines of bridges all season long. Live spot and eels drifted tight to the stanchions and on the down-current side will catch, as will adult bunker, though they can be harder to control.

While spring and fall typically have better bass bites, bridges are some of the most reliable places to find stripers right through the hot summer months. In addition, if a cold-water upwelling occurs midsummer and the backwater temperature drops, bass will become more active. Any stage of the tide can be effective, though falling tide is often slightly better in estuaries. Anglers who fish daily will learn which tides are putting bass in the boat, but if they can match the best tide scenarios with dawn and dusk, the chances of a terrific bridge bass bite exists.

Many bridges have lights that illuminate waters at the end of the abutments. The lights draw the baitfish, which draw stripers. The bass can be seen feeding as they dart in and out of the lights, which is a great opportunity to throw small soft plastics, paddletails, and plugs. Presentations that are similar to the small baits the stripers are gorging on are the best bet. Casting within the lit area is fine, but firing lures into the water just on the perimeter of the brightest lights occasionally works even better. Boats that take a stealth approach have a greater success rate than those that disrupt the night’s quiet with a motor churning within the feeding zone.

Fluke

Summer flounder can be found anywhere within the bridge environment and anglers should fish there similarly to an offshore wreck. Bait should be drifted close to the structure and tight to the base of the abutments because many fish hold extremely close. Gullies and dips form around the base structure, making for prime feeding spots. Secondly, boats should drift directly downstream of the bridge pillars, where fish wait for unwary bait to be washed their way in the confused currents. Those potholes and gullies mentioned earlier are fluke magnets. The boat will also drift slower here during the fastest part of the tide, although a vessel not using a motor of some sort will likely spin in the eddies. Under the bridge and anywhere between structure should also produce hefty fluke. Yes, the summer flounder are drawn to the bridge confines, but once they are in the vicinity, there can be some level of randomness between major structure zones. Basically, no area around a bridge should be unchecked and “undrifted” for summer flounder.

Live baits such as large minnows, peanut bunker, or spot do a lot of damage on a naked hook that matches the size of the bait. A 1-ounce bucktail tipped with a 6-inch Berkley Gulp Grub bounced along the bottom can be deadly along bridges. Braided line of 20-pound test is standard for this fishing, though gutsy fishermen use 10-pound-test braid in order to reach the bottom with the lightest possible jigs and bucktails.

Skippers owning vessels equipped with trolling motors can use them to stem the current and present baits just a little more slowly when drift speeds go above 1.5 mph. I prefer speeds from 0.5 to 1 mph around bridges so that larger, smarter fish get a good look at the offering. Boats that don’t have a trolling motor can back-troll and kick their engine in and out of gear in order to slow the speed. In fact, speed changes often entice hungry fluke since the presentation looks like a bait trying to flee the scene.

Like tog and sheepshead, fluke bite best around bridges when the water is clean and clear. Stable water temperatures that aren’t fluctuating day to day based on heavy winds are best to spark a bridge fluke bite

Other Bridge Fish

Black sea bass also pile up around bridges and can be caught on just about any live, dead, or synthetic bait. While bridges in southern New England are likely to hold keeper sea bass, the further south you fish, the inlet and backwater sea bass tend to be smaller. In South Jersey, you’d be hard pressed to get any keeps on the backwater pilings.

Weakfish and bridges have a funny relationship. Keeper to tiderunner fish do show a liking to some bridges and can be found in schools there when their preferred forage and clean water match up. Squid, cinder worms, and dense schools of baitfish stimulate a weakfish bite around bridges. Many don’t seem to hold any weakfish, but if anglers can figure out which ones do attract the trout, they can really rack up nice fish.

Bluefish hunt near bridges when baitfish hang in the shadow lines during daytime hours with a high sun. Blues that work the schools of hapless bait generally run small in size.

Related Content

Striper Fishing Backwaters with Live Eels

Leave a Reply