Deep Fly-Fishing Tactics

To catch more stripers on the fly, sink down to their level.

Guides and charter captains don’t stay in business by not catching fish. Customers may enjoy a pretty sunrise and an enjoyable day on the water, but fish brought to the net brings repeat business and enviable reputations. That means choosing fly-fishing techniques that are proven to catch fish day-in and day-out, all year long, are essential. For Capt. Joe “Maz Man” Mustari of Mazman Charters, going deep is his time-tested fly-fishing strategy to fool trophy-size striped bass in Raritan Bay. His key to getting the fly presentation down deep is using integrated sink-tip fly lines, a tactic he’s fine-tuned to a science.

I recently had the chance to talk to Capt. Joe about catching striped bass on the fly and came away with a new appreciation for the magic powers of those fly lines. Maz, as his friends call him, has been fly fishing New York Harbor and Raritan Bay for about 35 years and specializes in catching trophy striped bass on fly tackle. “It surprises many fishermen,” he says, “that Raritan Bay and the waters surrounding New York City have some of the best striped bass fishing to be found anywhere along the East Coast.

“This body of water is shared between New York City and the Jersey Bayshore, and there’s plenty of bottom structure to hold bait and bass. In spring, I usually look for water temperatures to rise to between 47 and 50 degrees to begin my guiding season. That seems to be the magic temperature where stripers start getting more aggressive on flies, but this isn’t just a spring fishery—there’s good fly fishing all through summer and well into the fall. The bay is loaded with anchovies and bunker, which draws huge schools of striped bass, sometimes even until Christmas.”

To purists locked into a mindset that fly fishing has to be done on the surface or the experience is somehow diminished, they often ignore deep fishing with sinking or sink-tip lines; however, it’s their loss because the rewards are so exciting. A 20-pound striped bass pulls just as hard on a sink line as it does on a floating line—and they sure slap a grin on every fly fisher’s face when it’s time to pose with the catch. Other fly fishers may shy away from sinking lines or sink-tip integrated lines because they heard casting can be tough, but the learning curve is short. Deep fly-fishing techniques are easily and quickly learned.

Some fly fishers call deep fishing dredging, but Maz argues, “I never liked the term dredging because it sounds so negative. Going deep is a lot like blind casting, just like most mid-Atlantic and New England flyrodders do when surf fishing—wading a shallow bay or drifting along a salt marsh casting to creeks, holes, and sand bars. Fishing deep is a special technique to get a fly down to where the bass are holding in water anywhere from 10 to 25 feet just as we have in Raritan Bay and thousands of other good spots along the coast. It’s blind casting but in deep water and, in fact, ninety percent of the time, blind casting is the most common way to fly fish.”

Going deep has its roots on the West Coast, where fly fishers developed the shooting-head system that attaches premade heads (sinking, floating, or intermediate) to mono, braided, or standard fly-line running lines. Although they can cast a mile, Average Joe casters often had trouble getting off a nice, smooth loop, and sometimes had awful tangles in the running line. Jim Teeny, a West Coast steelheader, is generally credited with manufacturing the first integrated sink-tip fly lines where the head (body) was extruded over a common inner core and connected directly to the running line in a knotless, integrated transition—hence the name integrated line.

Maz is a big advocate of integrated sink-tip lines. He says, “I started with full-sink lines and had some success, but they’re tough to cast. My customers did much better once I switched to sink-tip lines; everyone was much happier. Almost any decent caster can quickly adapt to an integrated sink-tip line and cast it well enough to catch fish.”

Casting will be less stressful if you use a water haul to begin each cast. After retrieving the fly close to the rod tip where you can see it, Maz recommends, “Make a simple roll cast and as soon as the fly hits the water, pick it up and make a backcast, followed by a sharp haul on the forward cast to shoot all your line back out. This is much more energy efficient than trying to false-cast a heavy fly line several times.”

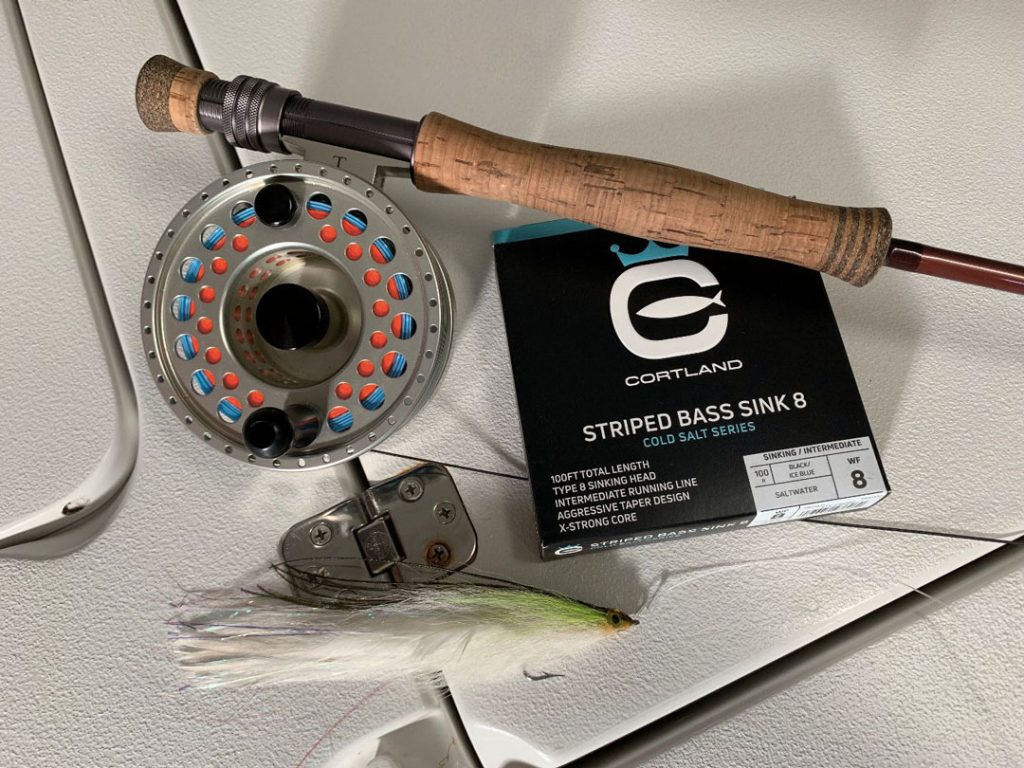

Mid-Atlantic waters are cool, even during the summer, so choosing a line that will handle and cast well in temperatures that range from 50 to 70 degrees is important. Capt. Joe says, “My go-to line is the Cortland Striped Bass Sink 8. It has a slightly thicker running line to reduce coiling, so it casts really well.” The Sink 8 is available in 8- through 12-weight line sizes, with grain ratings from 260 to 475. The total head length is 28 feet, but what’s really helpful for smooth casting is the 12-foot “step” in the transition between the body head and the intermediate running line that lets the casting loop unroll without dumping the fly, and just about eliminates any hinging effect.

CHOOSING THE ROD

For Raritan Bay and waters of similar depth and bottom contour, Maz recommends rods of 8- to 10-weight because they don’t tire the angler. There’s some difference of opinion between individual flyrodders about the ideal rod action. A stiff rod has the power to lift a fish from deep water, but it can be tough to cast comfortably. A soft rod lacks the lifting power but can be easier to cast. Maz has good advice, “My favorite rods are the TFO Axiom II and the slightly stiffer Axiom II-X. Most of my clients prefer the Axiom II for its ease and adaptability for most casting styles and its ability to launch heavy sink-tip lines. Others prefer Axiom II-X for its faster action and stiff butt section for making fast work of big bass.”

If you’re new at the game of going deep with sink-tip lines, you should know that sinking lines are labeled not only by their grain weights, but also by their sink rate. The grain weight matches the line to the rod (9-weight line to cast a 9-weight rod), while the sink rate indicates, in inches per second (ips), how fast the line will sink. A Type 3 sinks slowly at 3 inches per second while a Type 6 sinks at 6 ips and the Striped Bass Sink 8 goes down pretty quickly at 8 ips.

Maz recommends short leaders with the Sink 8 line. A long leader can be a bear to cast with sink-tip lines, and once at the proper fishing depth a long leader allows the fly to kite, or rise, in the water, which defeats the purpose of the sinking line. He says, “My leaders are anywhere from 4 to 7 feet long, and about half the leader length is a 40-pound butt section, while the other half is usually a 20-pound tippet. The factory loop on the Sink 8 is very dependable, so I just loop-to-loop the leader butt to the fly line. This simple leader turns over my most–used flies like chartreuse-and-white Clousers, Half and Halfs, or Pop Fleyes 3D flies when I need to imitate bunker.”

The stripping rhythm is also, important, Joe adds “Many fly fishers like to use a slow, steady pull, which is fine if you’re on a shallow grass flat, but for deep fishing, I prefer short, erratic, quick strips with a brief pause that’s just long enough for a bass to see the fly before it’s pulled away. This triggers the strike since they bite on the pause.”

According to Maz, one of the most important things about striper fishing with deep lines is learning the correct angle of your fly line. Stripers use tide and current to their advantage when feeding, so the key to presentation is to start the drift uptide and upwind of the feeding fish. Maz explains, “Present your fly in a way so that it is coming at you from no more than a 45-degree angle from the water’s surface. This angle seems to be the perfect presentation that stripers love and gets many more bites.

“Depending on wind and current, you may need to make a few casts around the boat to find this presentation angle. But once you discover the sweet spot, it almost feels as if the line is tugging back at you. You are now in perfect sync with the fly and able to detect even the slightest bite. When done correctly, there will be no slack in your line—which results in a solid hookset.”

Many deep bass are decent-sized fish that pull hard and get you into the backing pretty quickly. Short lifts of the rod tip and a rod angle of about 10 to 30 degrees will best use the rod butt’s power to beat the fish. For Capt. Joe ‘Maz Man’ Mustari, his day is made when an angler sings out, “Thank you, captain. That’s my personal best!”

HOW DO THEY DO THAT?

Fly lines float or sink because airlike micro balloons or micro-powdered tungsten dust are blended into the line’s coating. Think of a tennis ball and a stone, each weighing 350 grains. The air-filled tennis ball floats, while the dense stone sinks like…well…a stone.

Fly lines are rated by a numbering system based on the grain weight of the first 30 feet. An 8-weight line is supposed to weigh about 210 grains and should cast well on a rod rated as an 8-weight; however, integrated lines cast better one or two steps up in grain weight. An 8-weight rod matches to a 240- to 275-grain sink-tip; a 9-weight is about right with 280 to 330 grains.

With sinking lines, the mix of the dense material and flexible composition of the coating are blended to make lines of equal grain weight, but with different sink rates called Types. By blending the composition and diameter of the outer coating, a sink-tip line weighing 350 grains can be rated as a Type 3, 4, 6, or 8 sink rate.

The Type rating refers to the line’s sink rate in inches per second (ips). A Type 4 line sinks at about 4 ips, and a Type 8 at 8 inches ips, although actual sink rates may vary slightly depending on current and boat drift speed. If striped bass are holding at 15 feet, multiply 15 by 12 inches, then divide by the Type number of the line. A Type 8 line takes about 22 seconds to get to 15 feet.

Leave a Reply