The Scup Slinger

A love of scup led one man on a quest for the perfect porgy rod.

Last spring, I arrived at a unique and explosive intersection of my passions. Fishing, engineering, and researching merged in the act of building my first fishing rod. My love for catching porgies (or scup) collided head-on with my love for creating and testing limits. The journey started with catching a largemouth bass and ended in splinters two months later.

I caught my first porgy when I was 10-years-old on a family trip to Long Island. It was a welcome change of pace from the largemouth bass I always caught in my neighborhood pond. The ocean appeared so expansive and unconquerable to my 10-year-old eyes, but catching even the smallest porgy seemed a victory in the face of the unknown. Turns out, the sea is like my home pond, just a little bigger.

Fast-forward 17 years, I was living in New York City, and it’s my first time out on the Brooklyn-based Ocean Eagle. I’m hungry to catch, and porgies are on the menu.

The morning started slowly with a few dinner-plate-sized fish. We then continued our search until we were on porgy schools so thick that my high-low rig couldn’t hit bottom before a fish took my shrimp. I knew I was hooked. I fell in love with the rhythm of porgy fishing—the fish are fun, frantic, and delicious, especially when fried. Most people on the Ocean Eagle were using some variation of a high-low rig, but some in the front were slinging small epoxy and diamond jigs. That piqued my interest, but I had to wait until summer to explore those techniques.

At 4:45 on a pre-dawn 75-degree Saturday, I waited in line to rent a skiff from Jack’s Bait and Tackle on City Island. The stillness of the harbor sharply contrasted with my excitement for the day ahead. By 7:00, I watched my first porgy narrowly escape the jaws of two brown sharks. By noon, my boatmate and I had gotten a few dozen porgies up to 16 inches, and we were happy as clams. In addition to fantastic fishing, I really enjoyed the atmosphere out on the Sound. I loved drifting slowly over rocky humps and contours; I loved the sudden flurry of activity when we found porgies, landing four or five at a time. I loved that in my afternoon energy dip, I seemed to fish better, by way of lazily dragging my sinker as we drifted. It was the freest I had felt since my move to NYC.

However, something bothered me most of the day: my left wrist. I didn’t own a proper jigging rod and was using my 7’ largemouth casting rod, which has a short rear grip. As a result, every fight either had to be with two hands or with the miniscule rod butt dug uncomfortably into my chest. Additionally, the fast action on my bass rod meant I felt every erratic dive and turn of the porgy, further stressing my wrist. There had to be another way. I needed a rod with a longer rear grip to sit under my shoulder and a slower action to relieve stress while keeping fighting fish pinned. I also wanted the rod to handle a 1-ounce jig properly—not too heavy, not too light. I explored the market and found rods of all kinds, but nothing truly fit for this type of fishing. It was time to take matters into my own hands.

The Rod-Building Journey

In May 2021, I met Billy Vivona of North East Rod Builders (NERBs), who I’d seen fishing with gorgeous rods. The grips were fitted with multi-colored inlays. The decorative wraps had creative designs with color that popped. Even the guides complimented the blank and wrap colors. Each rod was a sensory feast, and I felt an intense need to learn his methods. My ambition was not to build anything quite so complex and spectacular, but to craft something with a similar level of precision. In January 2022, I got the chance to learn the NERBs method. We went through the process of spinning the rod, attaching grips and reel seats, choosing guide types, sizes, and spacing, then wrapping the guides and applying epoxy. This lesson was all I needed to get my feet wet.

Two months passed as I pondered what to build. I didn’t know if I would like rod building yet, but it had all the marks of something I’d enjoy: craftmanship, beauty, expression, risk, and an end product useful for a hobby I love. This was my chance to build lighter, more finely tuned designs than I could find in tackle shops. There’s nothing like using the exact tool for the (fishing) job, so I knew what I had to do.

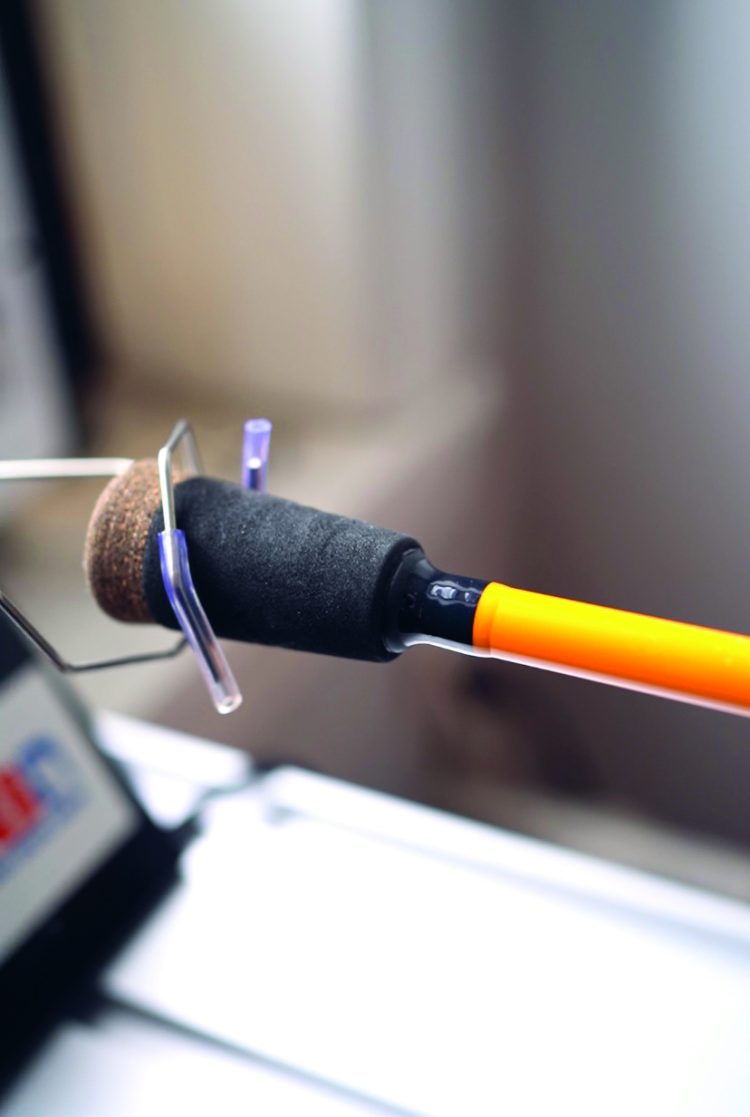

I wanted to keep my first rod visually simple, so I chose a color scheme of orange and black. The hardest decision was which blank to purchase. I had recently come to prefer 7’6” blanks for jigging and casting, and I knew I wanted something with a slower action than the rod I’d bought the summer before. I settled on a light power, medium-fast action 7’6” blank. To minimize weight, I chose a split rear grip with a 3-inch foregrip to handle hooksets.

Since I exclusively fish low-profile casting reels, I had to choose between conventional guide placements or an acid (spiral) wrap where the guides start on top and end on the bottom. For increased stability with heavier fish, I went with an acid-wrap guide setup (and have done so on every rod since). To increase leverage and decrease wear on my wrist, I chose to place the reel seat 15 inches above the butt of the rod (in hindsight too far—I went 13 inches the next time). In the end, I had an extremely lightweight, simple, well-balanced jigging rod. Above all, I loved it because I made it. The Scup Slinger had arrived.

Field Testing the Scup Slinger

I had been dying to get the rod on the water from the moment I had ordered the parts. On April 2, the water was barely thawed and the fish were lethargic, but I managed to test the casting at my first freshwater stop. The slower action of the rod blank took time to adjust to and forced me to slow my casting motion to accommodate the additional flex. The rod provided decent action on the soft-plastic jerkbaits I was using, but it didn’t possess the familiar snap of my fast-action rods.

At my second stop, I switched to a small swimbait and immediately felt the thump of a largemouth. I paused for a three-count, then swiftly set the hook. However, I couldn’t feel much on the end of the line and wondered if the Scup Slinger’s first catch had escaped. Five cranks later, it began to strip a few inches of drag and I was assured I had a fish on. Fifteen seconds later, I had a 15-inch largemouth in hand. The Slinger was not perfect in freshwater applications, but it helped me convert the only strike I had that day. My first rod build was a success.

Six weeks later, I finally had a chance to assess the Slinger against porgies; it was an enjoyable day of fishing, but a poor day for porgies. Nonetheless, the rod handled small blackfish to 15 inches with ease, managed a 22-inch fluke, and held on for dear life in battle with a spirited 21-inch striper. The blackfish were an adventure since each repeatedly dove back toward the craggy bottom they call home. I left that day knowing that the Scup Slinger was close to great, but with the realization that the blank was too light, leaving most of the fighting to the butt section and drag.

The Beginning of the End

Three days later during a quick stop to a local shore spot, I brought the Slinger to see if it was up for the challenge. Ten minutes into fishing, my white bucktail got slammed and the fish began to run, and run, and run. This wasn’t the usual schoolie bass. I managed to turn the fish and gain half my line back before it turned and ran again. This battle repeated four times, although when it finally surfaced, I met a bass well within the slot limit. My friend, Pete, lipped it and brought it onto land. The Slinger proved resilient through a brutal seven-minute fight with a fish well outweighing its capacity.

My next time out on a friend’s boat, we were jigging for fluke with 1½ -ounce jigs. This was an opportunity for the Slinger to shine! Or so I thought. Four hours in, I felt a typical fluke tap, let it eat, wound up for a homerun hookset, and CRACK! Suddenly, I lost all leverage and saw most of my rod sliding like a zip line down toward the water. My eyes widened and my neck tensed as a cold chill shocked my system. The Scup Slinger had departed.

I expected sadness to arrive at some point, but it never did. Sure, I destroyed my first build, but I had found the limits of that rod. Through testing it, I’ve gathered data to apply to my next build. The Scup Slinger 2.0 will have a stronger blank with a similar action, a couple inches less of rear grip, and one or two fewer guides. Another opportunity to test the limits awaits, and I’m psyched for it.

Related Content

Platter-Sized Porgies at Jessups Neck

2 on “The Scup Slinger”

-

Moses Leete’s Island Special Porgy BLT red onion& white toasting bread.

-

Daniel Pritchett Come fishing with the warriors on YouTube Rhode island

Leave a Reply