Offshore Nights: Gear, Safety and Weather

Meticulous gear preparation and safety practices are essential precursors to any successful trip offshore, especially under the cover of night.

Now that we are firmly into midsummer, the Northeast’s offshore fishery is full bore. August is traditionally the month the night bite in the canyons picks up. A typical 24- to 30-hour canyon trip includes an 8-hour segment of night fishing. My goals on any canyon overnight are safe boating first, 2 to 3 bites on the overnight drift, and figuring out where to troll at first light. I also want to optimize crew rest so everyone on board gets at least 3 hours of sleep during the dark.

When I first started canyon fishing 25 years ago, the night was an afterthought, a hope of a tuna flurry while tied up to a high flier, and more often than not, a long sleepless night for me. As my experience and expertise progressed, nighttime is a calculated plan to give us a serious shot at a swordfish and at least one opportunity per night at tuna under the boat.

The dark is also a world full of wonder between the brilliance of the night sky offshore without urban light pollution and the magic of seeing what might swim through the underwater lights at 1 a.m. Fireballs, meteors, and the Milky Way above; sharks, mantas, porpoise, swords, and tuna in the lights below; crazy kinds of bait attracted to the boat—to me, nothing beats standing the midnight watch alone on a calm and clear night. Here are some of my thoughts on how to turn the nighttime offshore from a necessary evil to a relaxing and entertaining part of a trip.

Crew Rotation

My crew seems to be made up of three types of people. First, there is the guy who needs his straight 8 hours of sleep, goes down to the cabin at 9 p.m. and is up and ready for the dawn troll at 5 a.m., but won’t roust out of a bunk even if we were being run down by the Titanic. The second type is the night owl who pounds an energy drink or two at 9 p.m., insisting that he is going to stay up and watch the spread all night long. He’s the guy I find dozing in the cockpit at 3 a.m. when the radar alarm wakes me up, beeping about the freighter closing at 16 knots 2 miles out. The third type of crew member understands a watch rotation, commits to a certain schedule, and can be counted on to do his job for 2 to 3 hours before going below for well-earned rest.

I can’t force one type of crew member to behave differently. It is necessary to set up a crew rotation that works for everyone, gets every person on board 4 to 5 hours of sleep overnight, and most important, an alert and active mind is watching both the spread as well as radar, weather, and sea conditions. In a perfect world, there would always two people on watch, one fully alert on the deck or at the helm, and a second dozing on call as needed. As a captain, I must work with the crew I have and set up a 2- or 3-hour rotation so everyone gets some rest that works with their sleep cycles. I have one crew member I have fished with for 15 years who is the first type. I’m not going to stop him from his “bunk time,” but do assign him the first watch, where he stays up till 11 or so while I grab some rest. I have a couple night owls I know are good till 2 or 3 a.m. Between those two types, I can get three hours of sleep early in the evening and be up at 1 a.m. to spell one of my tired night owls.

Watch Standing

Let’s talk about watch standing. You are offshore to fish and an important element of a canyon trip is the night segment. Having 3 to 4 good baits in the water, being alert to life around the boat, and marks on the fishfinder are the difference between those 2 or 3 night bites and a long and quiet night. A good crew knows to check baits, keep an eye on the fishfinder, work the flatlined baits, and jig on marks to make the night bite happen. Tending the spread is important but only part of watch standing.

The most essential part of a night watch is safety at sea. That means being situationally aware of the sea and weather conditions, along with establishing a regular radar watch pattern from 1-mile range right out to 16 to 24 miles. A good radar crewman sees a freighter 12 to 16 miles away on the screen and is well aware of any upcoming high fliers in the next mile. A radar watchman also knows the distance of any boats fishing nearby and is quickly alert if one of the boats starts closing. He also understands the meanings of ship lights and can identify a ship’s course by the light pattern presented.

I have “wake me if” rules that mean my crew is to get me up if a ship closes within 4 miles, or if we get within a half mile of a boat or high flier. There is little more embarrassing than to be on watch on deck and have a couple rods go off screaming, only to find they are wrapped around the down line of a high flier that snuck up on us. There is nothing more frightening than to wake up to a freighter sliding by your beam at a half-mile range because the deck watch person wasn’t looking forward or watching radar. Both have happened to me in the past five years!

I also make night passages at a slow speed. In my early years of canyon fishing, I had no fear of waking at midnight to steam out in the dark at 25 knots, loaded with bravado and false confidence. Over time, I have learned the danger and fallacy of that approach. If I hit something at 25 knots, it is possible someone in the crew will be seriously injured and equally possible that the boat’s structural integrity will be compromised. Radar is not going to show me the object floating awash in 3-foot seas, and while FLIR will, I have a hard time staring at a 16-inch monitor of a wavy sea for hours on end. Will I see that floating piling two hours into my overnight watch? I doubt it.

Are you prepared to get a radio call out, muster your crew into a life raft in the dark, and abandon ship in 3 minutes or less? I’m not, and I have no intention of putting people I care about in danger. My approach for the past half-dozen years has been to steam until dark, then slowly chug through the night at 8 to 9 knots to arrive at my target location at first light with a rested crew and captain. We have 2-hour watch shifts and at least 2 people are sleeping at a time. On a typical night passage, everyone gets 4 to 5 hours of sleep and is ready to fish at first light.

Safety on the Drift – Don’t Tie Up!

I would like to address a pet peeve of mine for canyon fisherman no matter their experience level—DO NOT TIE UP TO SOMEONE ELSE’S OFFSHORE GEAR! If you are not prepared to drift the night or if the conditions are too rough, you don’t belong out there that evening. Troll the night away or chug home. Tying up to someone’s lobster pots is tying up to a chain of 10-15 pots worth tens of thousands of dollars and can affect someone’s ability to earn a living. Don’t do it.

I have both a sea anchor and drift sock on board. I can fish with the drift sock and the sea anchor is a survival-at-sea option. The drift sock is a 4-foot-wide cone and 50 feet of line that will turn a boat a crucial 15-20 degrees and lessen the rolling impact of a beam sea. A sea anchor is a 9- to 15-foot-wide parachute with 300 to 400 feet of line, a piece of chain, and swivels. It will bring the bow into the sea and stall out the drift, but fishing with one means your lines are under the boat. At this point in my life, if I need the sea anchor, its time to head home.

One very important point on using either: deploy them from the bow, not from either a midship or stern cleat. The bow is designed to handle a breaking sea, but the stern is not.

Weather Watch

A very important part of night fishing offshore is keeping an eye on the weather, especially for adverse changes. During the 2020 pandemic, both economic and political pressures have limited the resources going into offshore weather forecasting. Fewer planes and ships mean less data points to tie a weather model to reality. A NOAA forecast is 20 to 30 words for 10,000 square miles. The various weather apps—Fishweather, Windy, Buoyweather, or Windflow—all use the same short-range and long-range data to derive their models. A model is not real, it is a predication and not a guaranteed fact.

I typically snapshot the 3-hour wind maps on my phone before I leave and do my best to track reality with the model. When I see reality diverge (such as bigger seas or stronger winds), my internal radar goes through the roof. Before I set up for the night, I go through those saved maps and pull up my Sirius weather maps, then try to tie them together. If things change at night, I’m leaving. I have probably pulled the plug halfway through an overnight twice per year for the past four years as weather kicked up. If I see or hear thunder and lightning, I plot an exit path away from any fronts moving through. My crew knows to wake me if things degrade, though I often wake up when I sense the change in sea state and make an early decision to leave.

I love fishing at night but want to be smart about it. Things goes from fun to unfun very quickly when the seas build from 2 to 4, from 3 to 5, and the wind starts blowing a steady 15 knots. Run away and live to fish another day.

Safety on Deck

Fishing at night both inshore and offshore is a different world. The moon, the stars, and the sea surround the bubble of light and sound of the boat. It’s a wonderful experience to be on a dark and quiet boat 100 miles out alone with my thoughts. Over time, I have worked hard to simplify night canyon fishing as well as remove as many dangerous elements as possible.

I typically fish a 3- or 4-rod spread of swordfish baits, and after years of rigging in the dark, I switched to pre-rigging baits before the trip, vacuum-sealing and freezing them, then pulling them out as needed throughout the night. Having pre-rigged baits makes tending the spread throughout the night that much easier. Less work at night is always better.

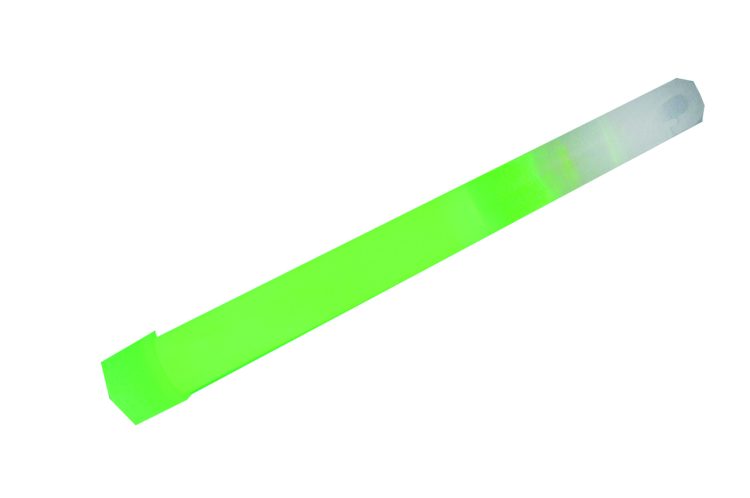

Two people typically fish in the evening, but by midnight, the long solo grind begins, so I try to limit it to 2-hour shifts tending the rods. When I am on deck alone, I wear either an inflatable life jacket or a float coat, and I always have a PLB (personal location beacon) and a light stick in my pocket. Additionally, all my safety gear has strobes. I have no intention of going overboard at night, but if I do, I intend to be found.

A bite at night is a crazy and quick maelstrom of chaos and action. Years of mistakes and lost fish taught me to have a gaff secured and ready on either gunwale and a harpoon rigged and ready in a fish-box rod holder in the center of my cockpit. Everyone on board knows where these are and how to bring them into action safely. Trying to find gaffs in the dark with a fish at the boat is a good opportunity for someone to get hurt. On my last trip, I was awakened 45 minutes after I had fallen into deep sleep. “Larry, we need you on the harpoon. Big fish!” I was up and booted in a minute, then had the harpoon in my hands 30 seconds after that, ready for action. About 3 minutes later, I made a short 2-foot throw into an angry swordfish, and the wheel man followed with a gaff to the head. We got that fish because we had prepared for a 10 p.m. fish at 8 p.m.

Knives are even worse at 2 a.m. I’ve been awakened three times over 20 years by someone asking for the first aid kit because he sliced his hand while cutting bait. A hard and fast rule on my boat is that bait is cut before dark, either on the way out or in down time while trolling.

All of these actions are planned to make fishing easy for the person on deck during a long overnight. We try to check the baits every hour, and if chunking, always have one or more buckets full and ready to go. Rig and prep before the trip or during the day. Focus on safety and fishing in the dark.

Boating a big fish in the dark is the pinnacle of a canyon trip; hauling a tuna or sword over the side at night is a triumph! However, 80 or 100 pounds of angry fish armed with a 3’ razor-sharp bill is extremely dangerous. The second a fish is on deck, the gaffs must be cleared from the fish and stowed safely out of the way. If it’s a swordfish, the bill must be controlled at all times. A pool noodle slid over it or a dock line looped from tail to bill will render it less dangerous.

Nighttime canyon fishing is a wonderful experience whether or not you actually catch a fish. The more you prepare in advance, the better the experience will be for anyone on deck and the better your chances of boating that 1 a.m. tuna or 3 a.m. swordfish. Put some preparation time in before the trip or during the evening troll to make night fishing safer as well as improve the chances of landing a fish in the dark.

Related Content

The Importance of Preventative Boat Maintenance

LISTEN: Swordfish by Day and Night w/ Capt. Larry Backman – On The Water

2 on “Offshore Nights: Gear, Safety and Weather”

-

David G Piazza Very good information for being prepared to fish at night and taking the proper precaution when on deck alone by wearing a life vest and strobe light. Too many times people are on a boat but they don’t know where the first aid kit is, flash lights, life vests, and what to do it something happens. Fire drills are done for a reason, when on a boat the captain should have drills, in case of fire, someone gets a hurt, or how to run the boat if the captain gets hurt. Be prepared the Boy Scout motto.

-

Darren Finch I am very interested in the Canyon over night trip.

What is the cost and What is the date

Please let me know.

Thank you

Leave a Reply